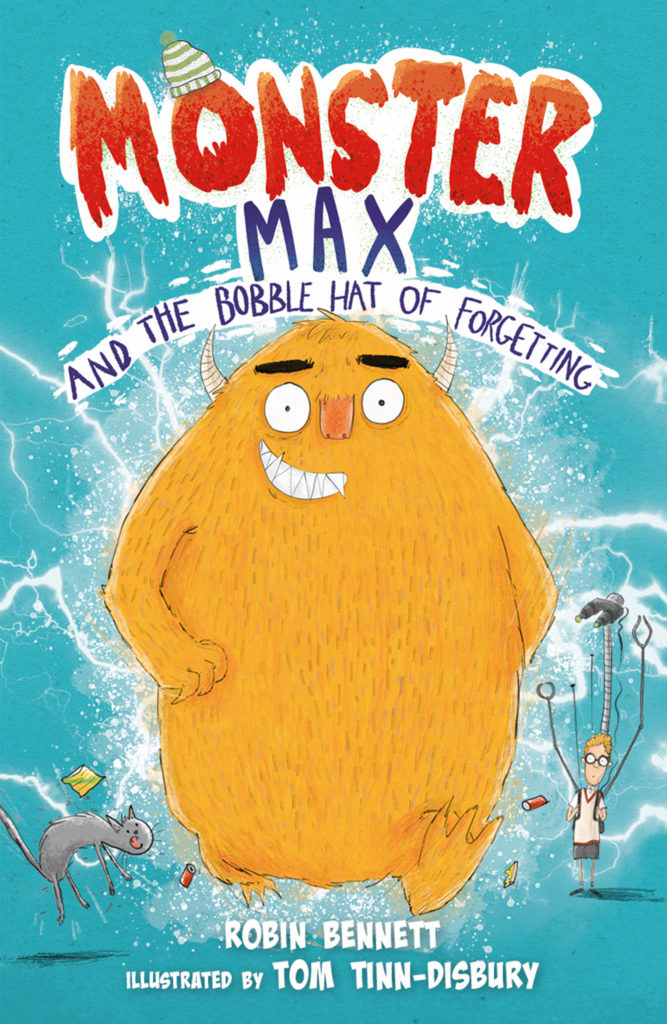

Monster Max and the Bobble Hat of Forgetting author, Robin Bennett, shares his rules for successfully writing for children…

1. Get rid of the parents

Preferably they are gone for good (eaten by something with teeth or tentacles whilst exploring the jungle is handy because it’s dramatic, implies an adventurous family streak and is a tiny bit funny). If you can’t bear to part with mum and dad in perpetuity, they can just be at the office a lot. Feel free to break this rule though, as I do in Monster Max.

2. Fantasy needs a lot of reality

Children will believe a lot, but you have to have rules and reality too. If dragons live in space (like in my book Space Dragons), if your hero has a magic hand that can point out treasure (The Hairy Hand), if we live alongside vastly talented and immensely powerful creatures without knowing it (Small Vampires), then that’s all well and good, but children need to know what their heroes have for dinner. And (above all), why all this stuff is happening.

3. Delete the first half of your first chapter

Seventy-seven times out of one hundred, your first thousand words are just you warming up. However much you cherished them that first morning you sat down in the spare room, their work is done. Loving is letting go. You don’t find many ten year-olds reading Faulkner or Flaubert – mainly because forty opening pages with just two full stops or a very detailed description of few streets in Rouen is dull. By way of example, for The Hairy Hand, my editor made me throw away my first two chapters and the story was much better for it. I still moaned about it, mind you.

4. Children deserve the best of us

At the end of the day, most kids just have to go along with whatever adults decide – and that’s fair enough: we’ve paid our dues, plus we’ve got the car keys. But the one area they are in charge of is their imagination: so make sure that when you write, you write for them and not for you. Also, BE KIND – children are more fragile than they let on and more forgiving than we deserve, books are often their only friends and comfort. If you must make a child suffer in a story, be sure it is for a good reason.

5. Character is king (or queen)

Plots don’t drive a good yarn, people do and children long for interesting characters…

5½.

… who they relate to (i.e. are like them).